The story of the Goods as a couple, professionals, and patrons of the arts and education points out the good karma of international education, but it started with the grim fate of Paul Fried, a nineteen-year-old Viennese, after the Anschluss of Austria in March 1938. Paul was separated from his family, arrested, imprisoned, then deported to Czechoslovakia. From there, he managed to emigrate to the USA taking a circuitous route via England. He had the good fortune of ending up at Hope College in Holland, Michigan, while his parents and two brothers ultimately were murdered in the concentration camps of the Third Reich. After his sophomore year at Hope, Fried enrolled in the US Army, where he served in the Intelligence Corps.

Editorial: Vienna, Paul Fried, David Good, J. William Fulbright, and the Good Karma of International Educational Exchange

16 April 2019Fulbright Austria is delighted to announce that the Rosemary and David Good Family Foundation has pledged $50,000 over a three-year period to support Fulbright Austria’s programs. Rosemary and David Good believe in the power of the arts, culture, and education to transform lives, so Fulbright Austria will dedicate their generous gift over the next three program years to financing and expanding its collaboration with the MuseumsQuartier in Vienna, which cosponsors unique Fulbright-Q21/MuseumsQuartier Artist-in-Residence awards. I will share more about this generous gift and this great opportunity with you below.

After the war, Fried returned to Hope College, graduated, and went on to earn a master’s in history at Harvard. He then served as a translator for the American delegation at the Nuremberg War Trails, completed a doctorate at the University of Erlangen, and returned to Harvard to work on a second doctorate, the completion of which he interrupted by taking a position in Germany working for the US Air Force Historical Research Association. In 1953, Fried joined the faculty of Hope College and became the legendary director of its then nascent international education programs shortly thereafter. In 1956, one of his first initiatives was to found a six-week summer program in his hometown of Vienna, which soon became a fixture in Hope’s programming and which he directed for twenty years.

More than 2,500 students have participated in the Hope College Summer Program in Vienna since its inception, and this is where two young undergraduates come into the picture: David Good, a twenty-one-year-old history major from Wesleyan University, and Rosemary Hekman, a music major and aspiring organist at Hope. In David Good’s own words: “In the summer of 1964, I first met and fell in love with my wife, Rosemary, when we were students in the Hope College Vienna Summer School Program. Two years later we were married, and three years after that we returned to Vienna for an entire year along with our 18-month-old daughter, Allison, thanks to an award from the Austrian Fulbright Program for the 1969–70 academic year.” The Fulbright award was truly a family affair: three for the price of one!

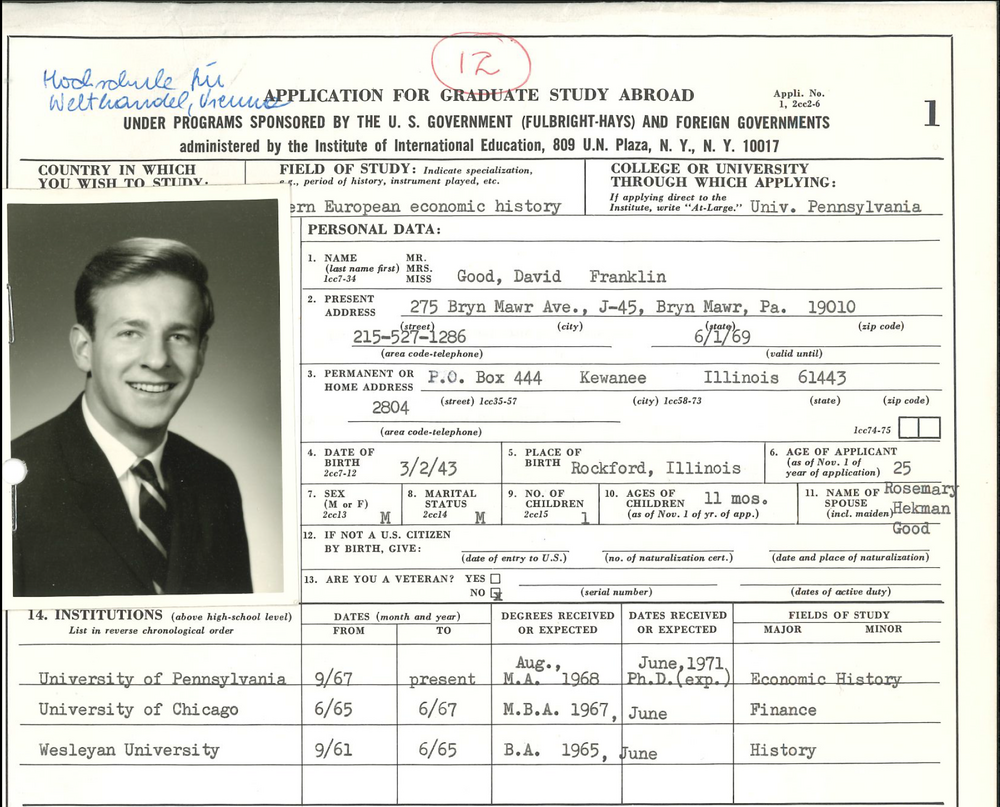

Between that summer in Vienna in 1964 and his return to Austria as a Fulbrighter in 1969, David graduated from Wesleyan, earned an MBA at the University of Chicago, and enrolled in the PhD program in economic history at the University of Pennsylvania: “In Vienna, Rosemary and I took full advantage of the city’s legendary reputation as a cultural mecca. We put Allison in kindergarten every morning so Rosemary could continue pipe organ lessons and have practice time. I spent most days in the archives of the Finanzministerium (finance ministry) searching through documents and gathering data for my dissertation on the economic history of the Habsburg Empire.”

Rosemary and David Good

Rosemary and David Good David Good's Fulbright application

David Good's Fulbright applicationThe Goods, of course, also took time to indulge in the conventional pleasures of Vienna: “In the evening we took full advantage of Vienna’s rich cultural offerings. We fell in love with opera and attended many thrilling performances in both the Staatsoper and Volksoper, and also attended concerts. On many evenings we headed up into the glorious Wienerwald with Allison to find one of our favorite Heuriger to drink wine and relax over dinner.”

Looking back, this is how David Good sees his 1969–70 Fulbright stay in Vienna: “My Fulbright year abroad set the stage perfectly for the next 30 years of my professional life. It gave me both the block of time I needed to track down and begin absorbing the sources I needed for my dissertation, and the confidence that I truly could carve out an academic career. At a deeper level my Fulbright year broadened my intellectual horizons by virtue of living in Vienna, in the midst of the diverse cultures of Central Europe.”

The Goods returned to the States in 1970, and David completed his PhD in economic history at the University of Pennsylvania, which led to his appointment as an assistant professor of economics at Temple University, where he taught economics and economic history and advanced to associate and full professor. His dissertation also laid the foundations for his book, The Economic Rise of the Habsburg Empire, 1750-1914 (University of California Press, 1984), which has the status of a standard work and the distinction of being translated into German just two years after it appeared.

David was on the cutting edge of a younger generation of revisionist historians who questioned widespread conventional assumptions about the Habsburg Empire. Traditional interpretations were based on the premises that the empire was a backward political and economic entity that was doomed to fail due to its political retardation and economic backwardness, and these premises, in turn, gave the collapse of the empire an air of inevitability. Ten years in the making, his wide-ranging, synthetic overview of the economic development of the Habsburg Empire reflects his command of primary sources as well as a vast body of secondary literature. He argued that the empire—although uneven in its economic development—was more modern and economically successful than previously believed. His innovative revisionist approach has guided much of the research on the Habsburg Empire since the 1980s. Ultimately, the Habsburg Empire was a more liberal, progressive, and successful polity than its many detractors would have us to believe after its not-so-inevitable collapse in 1918.

In the early 1980s, David’s career at Temple University also enabled him to return with Rosemary to Vienna every summer for five years as a faculty member in the Hope College Vienna Summer School, where they had met as undergraduates twenty years earlier. In 1990, David and Rosemary left Philadelphia for an appointment as director of the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS) and professor of history at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. He served as the CAS director from 1990 to 1996 and the chair of the Department of History from 2000 to 2003.

David Good’s career is exemplary because of the Fulbright Program’s major contribution to the development of Austrian studies in the United States. Several Austrian Fulbrighters have played the same role in the development of American studies in Austria. He was the first successor of William E. “Bill” Wright, the founding director of the CAS in 1976, who was a generation older than David. Bill’s career as a specialist in Austrian history began, like David’s, with a Fulbright grant in Vienna in 1954–55. David was succeeded by Gary Cohen, another Fulbright-Hays grantee, who served as the CAS director from 2001 to 2010. In 1987–88 Howard Louthan, the current CAS director, was a participant in the US Teaching Assistantship program that Fulbright Austria has managed for the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education since the early 1960s, and I was in the same program in 1977–78. Such is the “Fulbright ripple effect.”

It would be difficult to recapitulate briefly the many stations of David Good’s career, but I attempt to do so by limiting myself to a few examples. He published 25 articles in professional journals, edited books, and authored 35 book reviews. He served as the executive editor of the Austrian History Yearbook, 1989–1996 and 1999–2001, and he was responsible for the innovative topical programming of a number of international conferences under the auspices of the CAS that addressed a wide range of topics beyond the conventional realm of Austrian or Habsburg studies, including Kurt Waldheim, globalization, women in Austria, the economic transformations of East and Central Europe, and nationalism and empire. David also edited or co-edited the books that emanated from these events. He also served as the chair of the history department at the University of Minnesota for three years before becoming professor emeritus in 2007.

Since then—as a kind of homecoming—he has been involved in teaching, research, and publication focused on the history of the Midwest. David grew up in Kewanee, Illinois, and he has come a long way since then. This is his retrospect in his own words: “My Fulbright year was certainly a profound experience in its own right. For me, though, I believe the year served as the critical launching pad for my entire academic career and the various associated roles I have played over time.”

Fulbright Austria wishes to thank Rosemary and David Good for their exceptional support. We will dedicate their generous multi-year gift to enhancing Fulbright Austria’s collaboration with the MuseumsQuartier (MQ) in Vienna. Since 2008, Fulbright Austria has been fortunate to have its offices in the MQ and to be included in Q21, an umbrella organization for a network of 50 artistic and cultural initiatives. Since then, Fulbright Austria and Q21 have also cosponsored Fulbright-Q21/MuseumsQuartier Artist-in-Residence awards, which provide artists with an apartment/studio on site as well as a travel grant and an award for a two-month stay. These awards have been enormously popular—garnering the most hits in the art awards category on the website of the Council for International Exchange of Scholars, which handles the front-end part of the process of applying for US scholar awards—and the support of the Rosemary and David Good Foundation will be used to increase the number of these awards to three per annum as of the 2020–21 program year (with applications due by September 16, 2019).

(l. to. r.) The late Bill Wright, founding director of the Center for Austrian Studies (1977–88) with some of his Fulbright successors—Prof. David Good (1990–1996) and Prof. Gary Cohen (2001–2010)—along with Prof. Gerhard Weiss (1999–2001)

(l. to. r.) The late Bill Wright, founding director of the Center for Austrian Studies (1977–88) with some of his Fulbright successors—Prof. David Good (1990–1996) and Prof. Gary Cohen (2001–2010)—along with Prof. Gerhard Weiss (1999–2001)

Lonnie R. Johnson

Executive Director

PS: I also want to remind all alumni, friends, and associates of the Austrian-American Fulbright Program who are US citizens that April is advocacy season! The administration’s budget proposal for fiscal year 2020 entails a crippling 54% cut to the Fulbright Program, so it is high time to contact your representatives in Congress to call for a restoration of the funding for Fulbright to the previous year’s level of $271.5 million.

Writing your representatives in Congress has real impact, and it is easy to do using the GovTrack website. Advice on how to best craft a short and convincing email to your congressional representatives—or how to contact congressional offices in your home state or Washington, DC, by phone—is available on our website here.